First Swordsmanship class free

Visit us at the Fulton Place Community League any Tuesday at 7:00pm for your first HEMA lesson.

We’ll hand you a sword and we can practice together!

Why Us

We practice the full range of Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA), with a special love given to the sword! Emphasis is placed on effective real-world techniques described in historical arms treatises. You can expect to study all period weapons including pole arms, swords, daggers, and hand-to-hand fighting. While we focus on the teachings of the great masters, Johannes Liecthenauer and Joachim Meyer, we are not afraid to learn from other sources.

If you seek an authentic martial arts experience in an inclusive atmosphere that emphasizes real-world techniques over stage fighting and repetitive forms, look no further than the Academy of European Swordsmanship.

Upcoming Events

From our Blog

A Martial Artist’s Critique of Movie Sword Fights

By Eric Lowe, guest writer

For me, the big thing that distinguishes great sword fights from good ones is technique selection.Long answer:

I really can’t count a fight scene as good if it doesn’t serve the story well. But let’s assume that we’re looking at scenes where the story is there.

I also don’t really care much about timing and distance. This is a big one, because timing and distance decide something like … I don’t know, 80% of exchanges all by themselves, and fancy techniques only work if they’re powered by a good sense of timing and distance.

But good fight choreography requires the timing and/or distance to be wrong. A well shot and edited fight scene will disguise that, but it’s never going to be right. Complaining about that is pointless. You might as well complain that movie gunfights aren’t filmed with live ammo. But as a result, good fight choreography is never going to look realistic. It is inherently incorrect in the most fundamental way.

Consequently, I try to judge staged fights on other bases when I critique their “realism.” Principally, I look at the moves chosen by the choreographer, and ask myself, “If the timing and distance were correct, would that move have made sense?”

There’s always room in there for characters to be choreographed to make mistakes, of course. Not every character needs to fence like an unflappable master. But for characters who are supposed to be good, I basically try to imagine that the timing and distance are correct and then ask whether, so imagined, the fight was good fencing.

The answer is usually no. I know people are going to ask what I think is a good movie sword fight, and the answer is: I can’t think of one. I’m not an afficianado of movie sword fights, so my sample size isn’t huge, but seriously: I can’t think of one. I can only think of individual moments or aspects.

Common flaws:

Poor Fundamentals. Many movie sword fights exhibit poor fundamental body mechanics. Enrico Toro did a great job explaining this in detail for the climactic Rob Roy fight in Enrico Toro’s Quora answer to How realistic was the sword fighting in “Rob Roy”? I don’t expect every stunt person or actor to be proficient with a live blade, but it’s often really bad. Imagine a movie fist fight where all the punches look like this:

A lot of movie sword fights are that bad with their basics.

Armor as Costume. I don’t necessarily mind armor failing at dramatically appropriate moments, by which I mean I am actually okay with things like swords stabbing through armored men, sometimes. But I consider it a mark against the choreography if people don’t act like they expect their opponent’s armor to work. If you use the exact same approach to a guy in armor that you use against that same guy in street clothes, I’m going to notice. I should be able to tell from the choreography that you consider his armor an obstacle to your weapon.

Fake Reach. As I said at the beginning, I understand that stage fighting requires distance to be wrong. But if one of the characters is supposed to have a significant reach advantage (like a spear vs. sword fight), I expect both characters to act like it. I want to see the one character having that uphill battle against the superior reach of the spear, and the other character trying to maintain or regain that advantage over the course of the fight.

Technique Selection. And here’s the big one: once you’ve done X, why is your next move your next move?

In theory you could analyze opening moves this way, but choice of opening move is so dependent on timing and distance that in practice I find it impossible. Virtually any move could be a correct opening move given a certain timing and distance, so it’s hard to critique in a medium where timing and distance are always wrong by design, and I usually give it a pass. But follow-up moves are easier.

Once swords have touched, options become significantly constrained in terms of what might make sense, because the distance between combatants is necessarily such that either can be struck with very little movement. You must maneuver yourself and your weapon(s) to keep your weapon(s) between yourself and his weapon(s), while simultaneously maneuvering your own weapon(s) between you and him so that you may strike him. There are a variety of ways to do this with any given weapon set, but there are many ways to do it wrong.

As an example, consider this video of Jon Snow fencing with a longsword (bastard sword, in Westerosi terminology):

At 0:08, Jon parries an overhead blow with his hand on the blade of his own, and then kicks his opponent. Why? Why doesn’t he stab him, instead, or clock him in the ear with his pommel? Both of those are follow-ups that are available to him; both would make more sense than a kick.

By contrast, at 0:10, Jon’s new assailant attacks him with an overhead blow that it seems is actually supposed to be too close, because Jon moves in under the attack and stabs his opponent. That makes sense (given that the opponent has made such an egregious error in his distance and timing), and it makes a lot more sense than, say, kneeing his erring opponent in the groin.

Again, I’m all for allowing choreography to include mistakes. The guy Jon stabs through the gut was clearly choreographed to make a mistake and die as a result, and that’s great. That mistake has a purpose (to emphasize Jon’s skill and heroism). Jon kicking the first dude is not a choreographed error; it’s an error in the choreography.

At 1:35, we get a big “hero” duel for Jon. It starts off with some back and forth stuff that’s all out of distance and at the wrong timing, but as I’ve said multiple times by now, I personally give that stuff a pass. But at 1:48, Jon launches into a sequence of cuts, each of which is parried by his opponent on the haft, and each of which he follows up by cutting around to the other side. That’s amateur hour stuff. If he’s going to cut around, he could just as easily cut at his opponent’s legs, which would be significantly harder to parry with an axe haft at sword-clashing range. He could also lever his tip in around the axe haft at his opponent’s face, or slide down the haft to strike his opponent on the fingers (which he could have been targeting to begin with, of course).

At 3:20, we have a pretty egregious example of bad camera angle and editing failing to hide the fact that Qhorin Halfhand is striking his blow to miss Jon: it completely collapses Jon’s parry, and yet sails right past his head. But again … it’s fight choreography; I’m okay with that. Contrast with the very next action, at 3:21: Jon and Qhorin have their blades locked together overhead at the hilt. What makes sense at this point? Jon could rotate his pommel through to smash Qhorin in the face. He could let his sword hang and wrestle Qhorin to the ground. He could use his crossguard to shove Qhorin’s sword aside and use the momentum of the shove to whip around into a cut at Qhorin’s head. But he does none of those things. He uses his crossguard to shove Qhorin’s sword aside and then … stumble backwards, for some reason. At 3:28 a similar situation obtains, and it appears that Jon actually does cut at Qhorin … though the editing makes it hard to tell.

One last example, showing what I mean by fake reach:

At 5:00, Jon faces an opponent with two knives. The fact that his opponent has two daggers makes this trickier than if his opponent only had one, but Jon is choreographed to have a significant reach advantage in this fight. Does he use it? Well … he does get the first blow in, at 5:09. That’s something. The next two actions of the exchange show him staying at sword distance while his opponent tries to close to knife range, and when the opponent finally does, Jon spins away. Good! Then, at 5:21, does he attack once his opponent clears the fire? No, his opponent moves first, and Jon … blocks for some reason, instead of stabbing the knife fighter.

I’ve chosen this example because it comes from a well-known show where the errors in technique selection are fairly easy to see. This is because the fight choreography on Game of Thrones is not especially good apart from the technique selection. It tells an okay story, but the physical performance and photography of it do a poor job of hiding the fact that the distance and timing are wrong. That likewise makes it fairly easy to see where the choreography itself is wrong, though.

If we wanted to, we could also critique all these fights for their horrific fundamentals (the technique of everybody in this show who uses a Westerosi sword is almost distractingly bad, and I actively try to suspend my disbelief about this stuff). But even if the fundamentals and reach were good, even if the photography and editing were better, these are still fights that have lousy technique selection, because the techniques choreographed too often make no sense.

Eric Lowe is the head instructor of Swordwind Historical Swordsmanship (swordwind.org) in Charlotte, North Carolina, USA, where he studies and teaches Kunst des Fechtens and Bolognese fencing.

The HEMA Scholar – new AES book

Books on HEMA add credence and authority to how one is perceived as an instructor. Maybe it works that way for a whole school, too. I’ve been meaning to write a book for many years, and even have a few outlines completed, but never seem to find the time to complete any of them. Well, until now. I can’t take full credit for this one, though. It’s a collaborative effort of many people over several years’ time.

Books on HEMA add credence and authority to how one is perceived as an instructor. Maybe it works that way for a whole school, too. I’ve been meaning to write a book for many years, and even have a few outlines completed, but never seem to find the time to complete any of them. Well, until now. I can’t take full credit for this one, though. It’s a collaborative effort of many people over several years’ time.

Part of the AES curriculum includes scholarly efforts. Members are required to contribute to our knowledge of Western Martial Arts in order to progress past the level of Initiate in their martial ranks. We call these scholar projects. They can be lessons, including a proper lesson plan and notes for the class; an essay; or a photo-essay. Most members choose to do these before they even attain the rank of Initiate, and many do more than one long before it’s required. I guess we inspire each other this way!

For years we used to post every project online, but that stopped a few years ago. I’m not sure why…

This past August I took the time to compile several of these scholar projects into a book called The HEMA Scholar and made it available on Amazon. Have a look, see if it’s something you’d like (buy it if you like), and even post a review (as long as you’ve read the book).

There are plans to keep this going as a series. There are many more scholar projects that are worthy of publishing in a book that we have in our archives, and so making more books from these is certainly in the works. This one, the first volume, has a wide variety of articles in it, as well as some small side articles that include tips interpretations on martial arts, general HEMA, and fitness.

There are plans to keep this going as a series. There are many more scholar projects that are worthy of publishing in a book that we have in our archives, and so making more books from these is certainly in the works. This one, the first volume, has a wide variety of articles in it, as well as some small side articles that include tips interpretations on martial arts, general HEMA, and fitness.

Oh, and if you have suggestions for future articles, we’re certainly interested in knowing what those are!

2018 Tournament Winners

Open Steel Longsword

| 1 | Ashley Coe | The Forge Western Martial Arts |

| 2 | Joseph Paches | Academy of European Swordsmanship |

| 3 | Kevin de Ridder | Blood and Iron Martial Arts, Burnaby |

| 4 | August Sieben | Academy of European Swordsmanship |

Sidesword

| 1 | Tony Huang | Blood and Iron Martial Arts, Burnaby |

| 2 | Lars Le Gras | The Forge Western Martial Arts |

| 3 | Joseph Paches | Academy of European Swordsmanship |

| 4 | Roman Frolov | Academy of European Swordsmanship |

Women’s Longsword

Random-mixed weapons

| 1 | Joseph Paches | Academy of European Swordsmanship |

| 2 | Thora Jensdottir | The Forge Western Martial Arts |

| 3 | Tony Huang | Blood and Iron Martial Arts, Burnaby |

| 4 | Mark Winkelman | The Forge Western Martial Arts |

Tournament Champion was Joseph Patches (The AES), for which he received a Kvetun Federschwert donated by Sword Gear.

Sportsmanship award was to Par Parmar of Blood & Iron Martial Arts

Ragnarok – HEMA Tournament in Rimbey

The AES has it’s first hosted tournament of 2018 at our Rimbey chapter on June 23 at Rimbey Community Centre, starting at 10:00 am. This is Rimbey’s third tournament, and will include three events: steel longsword, steel sword & buckler, and synthetic Dane Axe. This is one of the tournaments that count towards the Prairies Historical Fencing League’s annual championship. Last year the PHFL champion got a beautiful trophy Fedeschwert courtesy of SGT Blades Inc. We’re not sure what the prize will be this year.

The AES has it’s first hosted tournament of 2018 at our Rimbey chapter on June 23 at Rimbey Community Centre, starting at 10:00 am. This is Rimbey’s third tournament, and will include three events: steel longsword, steel sword & buckler, and synthetic Dane Axe. This is one of the tournaments that count towards the Prairies Historical Fencing League’s annual championship. Last year the PHFL champion got a beautiful trophy Fedeschwert courtesy of SGT Blades Inc. We’re not sure what the prize will be this year.

As well, our Rimbey chapter offers some really nice prizes for their winners. The 2016 tournament champion, Johanus Haidner, won a beautiful knife, donated by Justin Skjonsberg. [insert picture here] The tournament fee is merely $60 and includes lunch!

June 24 there will be a sword & buckler workshop taught by AES Head Instructor Johanus Haidner. This will be a full day workshop, with a lunch break (lunch not provided). To attend the workshop there is an additional fee of $25.

Registration for tournament and/or workshop is here.

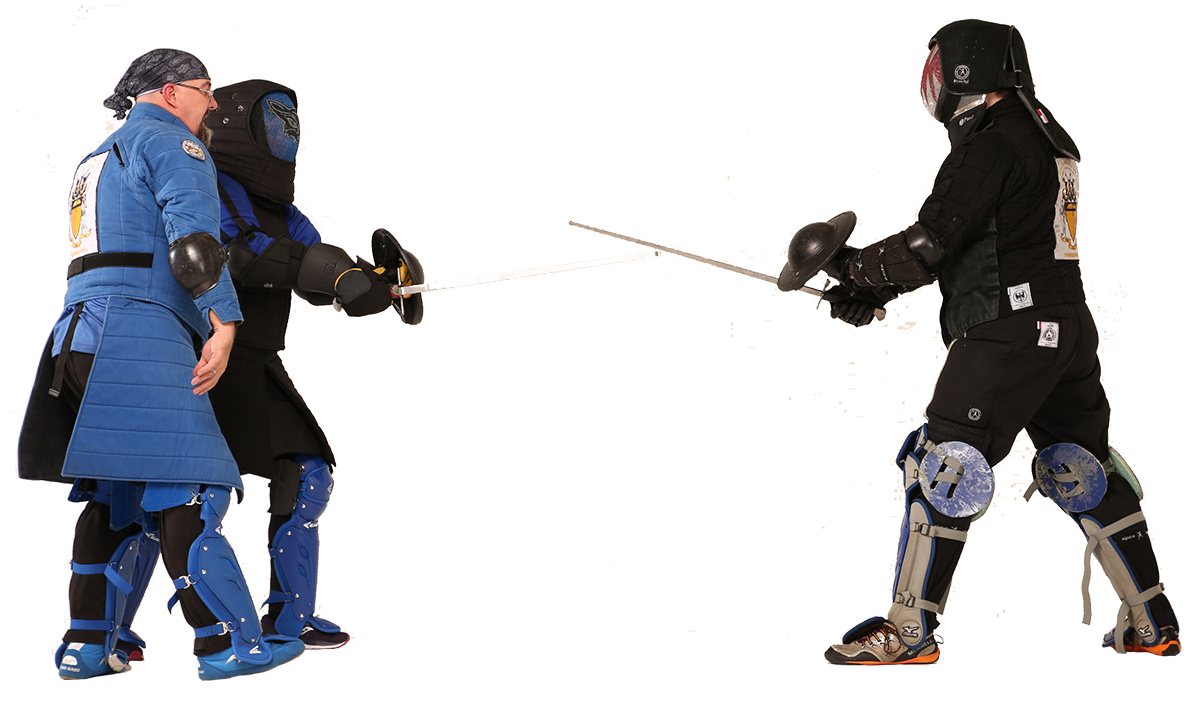

Reflection on HEMA Injuries

I had a lot of fun this past weekend at Anvil, a tournament ran by The Forge WMA in Calgary. The tournament was well organized, probably the best job I’ve seen them do yet. And the fighting was challenging and enjoyable – I think for everyone. I’m really looking forward to the remaining tournaments I’ll be in this year.

I didn’t place in the finals for either Messer or Longsword this year, but I kind of expecting that, since I haven’t truly competed in a long time. I made a few mistakes that made me angry at myself. The funniest of them – yes, funny – was when I grabbed a Messer being swung at my head. I have been drilling so much with sword & buckler that the movement to block was automatic. And I tried to block with the buckler three times in that one fight. Yeesh! I lost. And I sustained an injury from it, a severe bruise to one of my fingers. No big deal, as I have full movement, and the injury will likely be gone in a week.

This was one of four injuries I got this tournament. The least painful of them is the one on my ankle. This was a strange one, as the blow was mostly received on the upper part of my shoe. It was kind of a freak injury, and not likely to happen again. However, it does make me wonder about whether there should be protection on every spot where a bone could be hit. It did partially hit the bone on my ankle, but I didn’t feel that at the time. If it had hit there fully, instead of the top of my shoe and the soft tissue behind the bone taking most of it, I would have a fractured ankle. A couple of years ago someone else had his leg broken because he didn’t have any covering the couple of inches above his ankle and was hit there. And the power of the blow against the leg may also have been a factor. Since then PHFL rules dictate that there must some protective gear that comes down to the ankle, and that there must be no exposed skin. There are some issues with increasing the protective gear. But I’ll get into that at another time.

This was one of four injuries I got this tournament. The least painful of them is the one on my ankle. This was a strange one, as the blow was mostly received on the upper part of my shoe. It was kind of a freak injury, and not likely to happen again. However, it does make me wonder about whether there should be protection on every spot where a bone could be hit. It did partially hit the bone on my ankle, but I didn’t feel that at the time. If it had hit there fully, instead of the top of my shoe and the soft tissue behind the bone taking most of it, I would have a fractured ankle. A couple of years ago someone else had his leg broken because he didn’t have any covering the couple of inches above his ankle and was hit there. And the power of the blow against the leg may also have been a factor. Since then PHFL rules dictate that there must some protective gear that comes down to the ankle, and that there must be no exposed skin. There are some issues with increasing the protective gear. But I’ll get into that at another time.

I also have a bad bruise on the back of my shoulder. This one is also my fault. I get hit in that spot by the guy who inflicted this bruise in that area about one out of four of our fights. So, it’s obvious that I’m doing something wrong that makes me vulnerable to that strike, and he knows exactly what it is. I guess I have some more training to do! And that’s okay. One of the things that getting a little bit of pain can do is to teach. There’s the adage “no pain, no gain.” While it’s not true in most things, in this instance, the pain can teach – or at least motivate – one to figure out what the issue is that is causing one to continually get hit in the same spot. A good coach can help with this. The mistake in one’s sparring becomes particularly obvious when it costs a match during a tournament. And so, I know I have one thing (and probably a lot more) to work on before the next tournament.

My fourth injury is a bad lump, which left a mark and a swollen lump, on the top of my head. This was the hardest hit I’ve ever received to the head, regardless of what weapon has been used, the entire time I have been doing HEMA. And that’s a long time [I founded the AES in 1994]. The event was being fought with “lightsaber” rules. This means that no matter what, the first hit eliminated the other person, and after blows made no difference. I knew I was going to get hit and sacrificed that for the win. But getting hit with a light leather Dusack through a good HEMA mask shouldn’t hurt so much. And it certainly shouldn’t leave a wound, no matter how slight. This means the person I was fighting was hitting way too hard. The problem is how to deal with it. And that’s something I don’t have an answer to now.